On April 8, 2020, the convocation by Pope Francis of the Commission for the Study of the Female Diaconate was made public. At the closing of the Panamazon synod, he had promised to reconsider, and he has done so.

The previous one was a similar commission that had to be dissolved without major significance. We cannot avoid being surrounded by the same fear given the absences in the composition: all the members are European or American (as in the previous commission). The absence of the “global south” is striking. It seems that, when speaking of theology, nothing good can come from the south. It already starts from limited existential visions and this is serious, because from where you look at it determines a lot. When the reopening of this commission is the response to a request from the Amazonian peoples, its absence becomes even more noticeable.

I believe that there can be no other starting point than the recognition of equality between men and women. Gn. 1, 27: “So God created human beings in his own image, in the image of Godself, God created them, male and female God created them.”

The Final Document of the Amazon Synod affirms in No. 91: “Synodality marks a style of living communion and participation in local churches that is characterized by respect for the dignity and equality of all the baptized, men and women.”

However, this theoretical equality is constantly denied by reality. Male overrepresentation in the Church is an imbalance that distorts the image of God.

The entire symbolic message of ecclesiastical rites conveys the message that God is male. Official religious training reinforces it. The voices of women who demand equality in the Church are silenced. The general panorama allows us to question whether there is a real will to move forward. Let us trust that there is, and take advantage of this door that is opening. We must always have synodality as a horizon, not just arguing about the reproduction of what already exists, changing only the outward appearance.

The Spanish theologian Elisa Estévez López, in her teaching on women and ministries in the first communities demonstrates how the Christian and Mediterranean society sources of the first centuries were androgenic: they did not refer to women. The absence of female authorship is total; only the male vision has transcended. Therefore, our task is to reveal what has been hidden or marginalized by the sources.

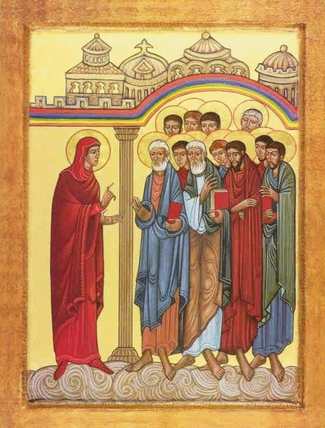

And even in that context, we find women in the New Testament texts. As Elisa Estévez points out so effectively, Christianity was taking root around families who offered their houses for communities to come together. Among them, many well recognized women: Prisca in Corinth (1 Cor 16, 19) and in Rome (Rm 16,15); Phoebe in Céncreas (Rm 16, 1-2); possibly Chloe in Corinth (1Co 1,11); Lydia (Acts 16, 14-15.40); Maria, the mother of Juan Marcos (Acts 12.12); Evodia and Síntique (Flp 4,3) are named by Paul as “collaborators”; and among those who have “laboured for the gospel” are Mary, Triphosha, Triphesa and Perside (Rom 16: 1-2). They are community leaders, identified -like men- as those who “preside over you in the Lord and admonish you” (1 Thess 5:12).

But all this is forgotten in the name of tradition. We will have to ask ourselves, in the name of what tradition.

It is clear to me, that the exclusion of women from any area of the Church is contrary to the spirit of Jesus, to the Kingdom that he inaugurated.

I am reminded of the words spoken during the Synod, by Sister Alba Teresa Cediel Castillo, of the Laurite Sisters, a Congregation founded to be with the Indigenous people- those who were dying confessed to the Sisters. Since they cannot formally give absolution, she stated that they simply leave it in the hands of God. Who will think that God does not forgive that person who has done all his inner process, simply because he was not lucky enough to have a priest at his side to absolve him? It is God who forgives. We must remember that “when two or more are gathered in my name, I am in their midst” (Mt. 18,20). The God of mercy assists us as brothers and sisters, we must not be afraid.

Another fact that cries out to heaven is the exclusion of women from the proclamation of the gospel. In fact, the great announcement of Christianity is the resurrection, and the first witnesses to whom Jesus entrusted such a message were women. One of the arguments to guarantee the authenticity of the resurrection is precisely that the witnesses were women; if it were a later invented argument, women would never have been chosen as witnesses, since at that historical moment women were disqualified as such. In this context, Jesus recognizes and affirms the primacy of women. Today, are we denying them that they bear witness to their experience of God in the homilies, let alone that they proclaim the gospel during the Eucharist? There is no reasonable explanation for this exclusion.

From repeating them so much with the same patriarchal mentality, the rites have acquired value by themselves, but have distanced themselves from the spirit of Jesus. Our liturgies are in need of conversion.

The commission for the study of the female diaconate has a narrow scope. But it is the door that is opening so we will have to walk the path with the most constructive attitude possible, without giving up the dignity of original equality.